When Fairness Meets Privacy

When Fairness Meets Privacy: A Double-Edged Sword in Machine Learning

This blog is based on and aims to present the key insights from the paper: When Fairness Meets Privacy: Exploring Privacy Threats in Fair Binary Classifiers via Membership Inference Attacks by Tian et al. (2023) 1. The study investigates how fairness-aware models can introduce new privacy risks, specifically through membership inference attacks. By summarizing the main findings and implications, this blog provides an accessible overview of the paper’s contributions and their significance for machine learning security and ethical AI development. For full details, refer to the original publication here.

Authors: Lagarde Vincent, Boyenval Thibaut, Leurquin Daniel

This image was generated using artificial intelligence.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Fairness or Privacy—Pick Your Poison?

- Algorithmic Fairness: A Noble Goal That Cuts Both Ways

- Membership Inference Attacks: The Silent Thief of Privacy

- The Birth of a New Threat: Fairness Discrepancy Membership Inference Attacks (FD-MIA)

- Reproducible Code Experiments: Illustrating FD-MIA

- Experimental Findings: How Fairness Opens the Door to Attackers

- The Future of Fairness and Privacy: Can We Have Both?

1. Introduction: Fairness or Privacy Pick Your Poison

It is double pleasure to deceive the deceiver. — Niccolò Machiavelli.

This paradox of attack and defense perfectly applies to the interplay between fairness and privacy in machine learning.

Imagine stepping into a high-tech courtroom. The AI judge, designed to be perfectly fair, renders unbiased decisions. But then, a hacker in the back row smirks—because that same fairness-enhancing mechanism just leaked private data about every case it trained on.

Fairness and privacy in AI are like the two ends of a seesaw: push too hard on one side, and the other rises uncontrollably. Recent research reveals a disturbing paradox: making a model fairer can also make it leak more private information.

This blog explores how fairness in machine learning, despite its good intentions, can introduce Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs). Worse still, it uncovers a devastating new attack—Fairness Discrepancy Membership Inference Attack (FD-MIA)—that exploits fairness interventions to make privacy breaches even more effective.

2. Algorithmic Fairness: A Noble Goal That Cuts Both Ways

Fairness in AI is like forging a perfect sword—it must be balanced, precise, and just. Researchers have developed in-processing fairness interventions, which modify the training process to remove biases in model predictions. These methods act like master swordsmiths, hammering out the unwanted imperfections in AI decision-making.

However, every sword has two edges. These fairness techniques do not just eliminate biases—they also alter how models respond to data. This change in behavior can create exploitable patterns that adversaries can use to infer whether a specific individual was part of the training data. In short, while fairness dulls one blade (bias), it sharpens another (privacy risk).

Mathematically, fairness interventions often involve introducing constraints into the loss function:

$$L_\text{fair} = L_\text{orig} + \lambda \cdot \mathcal{L}_{\text{fairness}}$$

where

- $\mathcal{L}_{\text{orig}}$ is the original loss function (e.g., cross-entropy loss for classification tasks).

- $\mathcal{L}_{\text{fairness}}$ is a fairness penalty term, which ensures that predictions are balanced across different demographic groups.

- $\lambda$ is a hyperparameter controlling the trade-off between accuracy and fairness.

Common fairness constraints include Equalized Odds, which ensures that true positive and false positive rates are equal across groups:

$$P(\hat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1, S = s_0) = P(\hat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1, S = s_1)$$

where $S$ represents a sensitive attribute (e.g., gender or race).

The fairness penalty can be incorporated during model training by adding it to the loss function, as shown in this training function. A penalty coefficient can be specified to control the impact of the fairness term. Setting the coefficient to 0 results in no penalty being applied to the loss:

def train_model(model, data_loader, optimizer, criterion, fairness_weight=0.0):

model.train()

total_loss = 0.0

for X_batch, y_batch, sensitive_batch in data_loader:

optimizer.zero_grad()

logits = model(X_batch)

loss = criterion(logits, y_batch)

# Fairness regularization: penalize different confidence (softmax probabilities)

if fairness_weight > 0:

probs = nn.functional.softmax(logits, dim=1)

# Compute average probability for each sensitive group

group0_mask = (sensitive_batch == 0)

group1_mask = (sensitive_batch == 1)

if group0_mask.sum() > 0 and group1_mask.sum() > 0:

avg_prob0 = probs[group0_mask].mean(dim=0)

avg_prob1 = probs[group1_mask].mean(dim=0)

# L2 difference between average prediction distributions

fairness_penalty = torch.norm(avg_prob0 - avg_prob1, p=2)

loss += fairness_weight * fairness_penalty

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

total_loss += loss.item()

return total_loss / len(data_loader)

While these interventions improve fairness, they also alter the confidence distribution of model predictions—a fact that attackers can exploit.

3. Membership Inference Attacks: The Silent Thief of Privacy

🔐 A Parallel with Cryptography Membership inference attacks (MIAs) are to privacy what brute-force attacks are to passwords. Instead of guessing a password, they test thousands of combinations to see which one is good.

MIAs work the same way: they analyze a model’s outputs to determine if a given data point was part of its training set.

A traditional MIA exploits confidence scores—the probabilities that a model assigns to different predictions. The intuition is simple: models tend to be more confident on data they have seen during training. Given a target model $T$ and a queried sample $x$, an attacker computes:

$$M(x) = 1 \text{ if } A(T(x)) > \tau$$

where:

- $A(T(x))$ is a decision function (often a threshold on the confidence score).

- $\tau$ is a predefined threshold.

Why Traditional MIAs Fail on Fair Models

Fairness interventions introduce more uncertainty into the model’s predictions. This causes:

- Lower confidence scores overall, making it harder for attackers to distinguish between training and non-training samples.

- More uniform confidence distributions, which means attackers lose their key signal.

Thus, fairness-enhanced models resist traditional MIAs. But this protection is not foolproof—a new, more dangerous attack lurks in the shadows.

4. The Birth of a New Threat: Fairness Discrepancy Membership Inference Attacks (FD-MIA)

If traditional MIAs are blunt weapons, FD-MIA is a scalpel. It exploits the discrepancies between a biased model and a fairness-enhanced one.

How does FD-MIA work?

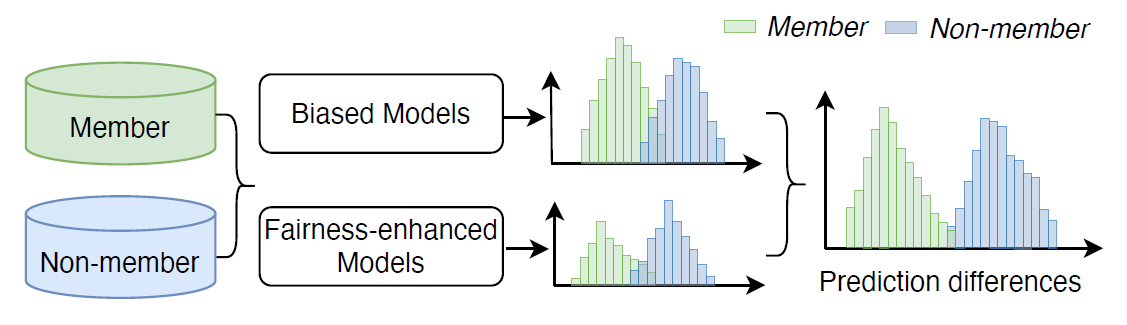

Fairness interventions shift model predictions differently for training and non-training data. This creates a gap between how biased and fair models behave for the same inputs. An attacker, armed with knowledge of both models, can exploit this difference to infer membership with high accuracy.

Mathematically, FD-MIA extends membership prediction by comparing prediction shifts between biased and fair models:

$$M(x) = 1 \text{ if } |T_{\text{bias}}(x) - T_{\text{fair}}(x)| > \tau$$

where:

- $T_{\text{bias}}(x)$ and $T_{\text{fair}}(x)$ are the predictions from the biased and fair models, respectively.

- $\tau$ is a threshold chosen by the attacker.

Figure 1: FD-MIA exploits the predictions from both models to achieve efficient attacks. From original paper.

The key insight is that fairness interventions cause systematic shifts in model confidence, creating a measurable pattern that attackers can exploit.

Here is an example implementation of the FD-MIA attack using a function that compares the prediction difference between two models against a user-defined threshold:

def fd_mia_attack(sample, biased_model, fair_model, threshold=0.1):

"""

Given a sample, compute the absolute difference between the

biased and fair model's softmax outputs for the positive class.

If the difference exceeds the threshold, predict membership.

"""

biased_model.eval()

fair_model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

logits_b = biased_model(sample.unsqueeze(0))

logits_f = fair_model(sample.unsqueeze(0))

prob_b = nn.functional.softmax(logits_b, dim=1)[0, 1]

prob_f = nn.functional.softmax(logits_f, dim=1)[0, 1]

diff = abs(prob_b - prob_f)

# In practice, the threshold can be tuned via shadow models or validation

return 1 if diff > threshold else 0, diff.item()

5. Reproducible Code Experiments: Illustrating FD-MIA

In this section, we reproduce the FD-MIA attack described in the original paper:

Data Generation and Splitting

The process starts with generating a synthetic dataset where a binary sensitive attribute influences the feature distribution. The target labels are computed using a logistic function, and the dataset is then split into training (member) and testing (non-member) sets to simulate membership inference scenarios.

Classifier Architectures

Two identical neural network architectures are defined:

- A biased baseline model trained without fairness constraints.

- A fairness-enhanced model, which incorporates a fairness penalty to balance prediction distributions across sensitive groups.

Training with Fairness Regularization

The function train_model allows the inclusion of a fairness penalty during training. For the fair model, this penalty—weighted by fairness_weight—is added to the standard cross-entropy loss to encourage prediction consistency across sensitive groups.

FD-MIA Attack Implementation

The attack, implemented in fd_mia_attack, exploits the absolute difference in predicted probabilities (for the positive class) between the biased and fair models. If this difference exceeds a given threshold, the sample is inferred as a training member. This approach leverages the core principle of FD-MIA: fairness interventions create prediction discrepancies that can be used for membership inference.

Evaluation and Visualization

The attack is evaluated by comparing prediction differences between member and non-member data. We visualize the prediction difference distributions to highlight how fairness-driven adjustments can unintentionally expose membership information.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader, random_split

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

torch.manual_seed(42)

np.random.seed(42)

# -------------------------------

# 1. Create a synthetic dataset with a sensitive attribute

# -------------------------------

class SyntheticFairDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, n_samples=1000):

# Features: two-dimensional points drawn from different distributions

self.n_samples = n_samples

self.X = []

self.y = []

self.sensitive = [] # sensitive attribute: 0 or 1

for i in range(n_samples):

# Randomly assign a sensitive group (imbalance can be introduced here)

s = np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.7, 0.3])

# Generate features from group-dependent distributions

if s == 0:

x = np.random.normal(loc=0.0, scale=1.0, size=2)

else:

x = np.random.normal(loc=1.5, scale=1.0, size=2)

# Label is determined by a linear rule (with some noise)

y_prob = 1 / (1 + np.exp(- (x[0] + x[1] - 0.5)))

y_label = np.random.binomial(1, y_prob)

self.X.append(x)

self.y.append(y_label)

self.sensitive.append(s)

self.X = torch.tensor(self.X, dtype=torch.float32)

self.y = torch.tensor(self.y, dtype=torch.long)

self.sensitive = torch.tensor(self.sensitive, dtype=torch.long)

def __len__(self):

return self.n_samples

def __getitem__(self, idx):

return self.X[idx], self.y[idx], self.sensitive[idx]

dataset = SyntheticFairDataset(n_samples=2000)

# Split into training (for model training) and attack evaluation (simulate member vs. non-member)

train_size = int(0.5 * len(dataset))

test_size = len(dataset) - train_size

train_dataset, test_dataset = random_split(dataset, [train_size, test_size])

train_loader = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=64, shuffle=True)

test_loader = DataLoader(test_dataset, batch_size=64, shuffle=False)

# -------------------------------

# 2. Define the classifier architectures

# -------------------------------

class SimpleClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim=2, hidden_dim=16, output_dim=2):

super(SimpleClassifier, self).__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim)

self.relu = nn.ReLU()

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, output_dim)

def forward(self, x):

out = self.relu(self.fc1(x))

return self.fc2(out) # raw logits

# Baseline (biased) model

biased_model = SimpleClassifier()

# Fairness-enhanced model: we add a fairness penalty to the loss (for demonstration)

fair_model = SimpleClassifier()

# -------------------------------

# 3. Train both models

# -------------------------------

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

# Train biased model without fairness penalty

optimizer_biased = optim.Adam(biased_model.parameters(), lr=0.01)

for epoch in range(20):

loss = train_model(biased_model, train_loader, optimizer_biased, criterion, fairness_weight=0.0)

# Uncomment to print loss: print(f"Biased Model Epoch {epoch+1}: Loss {loss:.4f}")

# Train fair model with a fairness penalty (fairness_weight > 0)

optimizer_fair = optim.Adam(fair_model.parameters(), lr=0.01)

fairness_weight = 1.0 # adjust to control trade-off

for epoch in range(20):

loss = train_model(fair_model, train_loader, optimizer_fair, criterion, fairness_weight=fairness_weight)

# Uncomment to print loss: print(f"Fair Model Epoch {epoch+1}: Loss {loss:.4f}")

# -------------------------------

# 4. Membership Inference Attack using FD-MIA

# -------------------------------

# Evaluate the attack on both training (members) and test (non-members) samples

def evaluate_attack(dataset, biased_model, fair_model, threshold=0.1):

attack_labels = []

attack_scores = []

# Assuming samples in train_dataset are members and test_dataset non-members

for sample, _, _ in DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=1, shuffle=False):

pred, diff = fd_mia_attack(sample[0], biased_model, fair_model, threshold)

attack_labels.append(pred)

attack_scores.append(diff)

return np.array(attack_labels), np.array(attack_scores)

# For demonstration, we use the entire training set as member data and test set as non-member data.

member_labels, member_diffs = evaluate_attack(train_dataset, biased_model, fair_model, threshold=0.1)

nonmember_labels, nonmember_diffs = evaluate_attack(test_dataset, biased_model, fair_model, threshold=0.1)

6. Experimental Findings: How Fairness Opens the Door to Attackers

The study conducted extensive experiments across six datasets, three attack methods, and five fairness approaches, testing over 160 models. To do this, they performed a comprehensive set of experiments involving:

Multiple datasets with different sensitive attributes (like gender or race),

Biased vs. fair model variants,

Three types of MIAs (including their novel FD-MIA),

Multiple fairness interventions

| Dataset | Number of Fairness Settings | Target Tasks | FD-MIA Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| CelebA | 3 settings (smile, hair, makeup) | 3 binary targets × 2 sensitive attributes | FD-MIA consistently outperformed other methods. |

| UTKFace | 2 settings (race prediction, gender prediction) | Race or gender, sensitive to the other | FD-MIA revealed privacy leaks even with balanced groups. |

| FairFace | 2 settings (race prediction, gender prediction) | Same as UTKFace | Most vulnerable dataset—biggest fairness shift = biggest privacy leak. |

The results were shocking:

- Fair models were significantly harder to attack using traditional MIAs.

- FD-MIA, however, dramatically increased attack success rates—fairness actually made models more vulnerable!

- The greater the fairness intervention, the wider the discrepancy between biased and fair models, making FD-MIA even more effective.

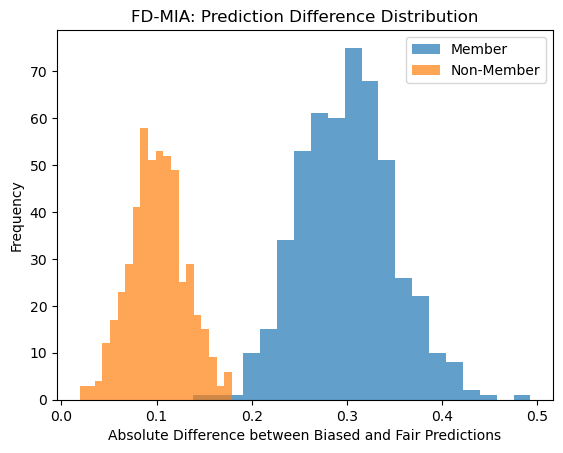

Our synthetic experiment further supports these findings. The histogram below illustrates the absolute difference between the predictions of the biased and fair models for both members (training data) and non-members (test data).

Figure 2: FD-MIA: Prediction Difference Distribution.

As expected, members exhibit a significantly higher prediction discrepancy compared to non-members. This clear separation highlights how fairness constraints alter model confidence differently for training and test samples—providing an exploitable signal for membership inference. In simple terms: making a model fairer may paradoxically make it leak more private information. A cruel irony for those trying to do the right thing.

7. The Future of Fairness and Privacy: Can We Have Both?

The million-dollar question: Can we balance fairness and privacy without sacrificing one for the other?

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. — Sun Tzu.

A better understanding of the link between fairness and privacy, as well as the potential and new attacks introduced by unbiased models, is already a solid step toward defending against threats. By understanding the underlying mechanisms, it becomes possible to counteract them.

The researchers propose two key defenses:

Restricting Information Access

- Limiting confidence score outputs reduces the information available to attackers.

Differential Privacy (DP)

By injecting noise into model training, DP-SGD (Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent) helps obscure membership information:

$$\tilde{g}_t = g_t + \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2 I)$$

where $g_t$ is the original gradient and $\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2 I)$ is Gaussian noise added to prevent membership inference.

While these methods help, they come with trade-offs: too much privacy protection can lower fairness and accuracy, while too little leaves models vulnerable. The challenge ahead is designing AI systems that can balance both.

💡 Alternative approach: Fairness-Aware Differential Privacy (FADP) adapts noise levels based on protected groups, balancing privacy and fairness.

References

H. Tian, G. Zhang, B. Liu, T. Zhu, M. Ding, and W. Zhou, “When Fairness Meets Privacy: Exploring Privacy Threats in Fair Binary Classifiers via Membership Inference Attacks”, arXiv e-prints, Art. no. arXiv.2311.03865. ↩︎