Robust or Fair

To be Robust or to be Fair: Towards Fairness in Adversarial Training

Authors: Maryem Hajji & Cément Teulier

Table of Contents

Abstract

This blog post retraces the study conducted in the paper “To be Robust or to be Fair: Towards Fairness in Adversarial Training” and written by Han Xu, Xiaorui Liu, Yaxin Li, Yaxin Li, Anil K. Jain and Jiliang Tang.

Their study is based on a simple observation: while adversarial training has been shown to improve model’s robustness, it also introduces several performances disparities among different data groups.

To address this issue, the authors present the Fair-Robust-Learning (FRL) framework that aims to reduce such unfairness.

Introduction

Nowadays, Machine Learning algorithms and Artificial Intelligence are becoming more and more omnipresent in all kinds of jobs. If many of these models are developed to replace human tasks, it is of key importance that they do not reproduce the same mistakes. In fact, human decision making can sometimes be considered “unfair”, a trait that must not be present in Machine Learning. But as we push our models to be as precise as possible, one question stands out: can we find the good balance between accuracy and equity ?

Diving into this topic, we focus our study on adversarial training algorithms. Indeed, it has been shown that there is a significant issue in adversarial training for deep neural networks: while such training boosts the model’s defenses against adversarial attacks, it unfortunately leads to significant differences in how well the model performs across various types of data. For instance, detailed observations on CIFAR-10 dataset show a non-negligeable difference in the model’s performance between “car” and “cat” classes (details of this example in our section 1.1).

This phenomenon raises concern on concrete topics like the safety of autonomous driving vehicules or facial recognition while also creating ethical problems by discriminating certain classes. To put a word on it, the authors have identified this issue as the robust-fairness problem of adversarial training.

1. Initial Analysis

We recall here the previous studies conducted by the authors that allowed them to identify the existence of the robust-fairness problem.

1.1 Previous Studies

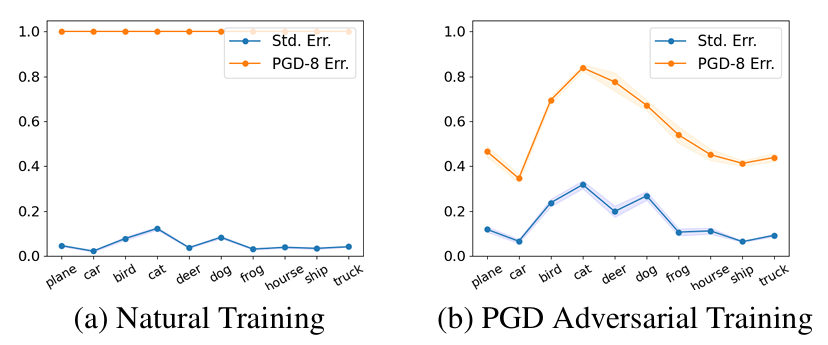

For their first analysis, the authors have decided to study algorithms like the PGD ( Projected Gradient Descent) adversarial training and TRADES ( Theoretically Principled Trade-off between Robustness and Accuracy for Deep Learning ) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The investigation is made using a PreAct-ResNet18 model structure under specific adversarial attack constraints. The results they obtained are as follows:

As we can see, natural training maintains a consistent standard error across classes and a consistent robust error rate when faced with 8/255 PGD attacks. However, in the case of adversarial training, some huge disparities appear. Going back to our introduction’s example with “cats” and “cars”, we observe that the standard and robust errors for “car” class ( respectively 6% and 34% ) are significantly lower than those of the “cat” class ( respectively 33% and 82% ). The results on the TRADES, altough not depicted here, also show some great disparities between certain classes.

To support this graphical study, the authors also present statistical evidence of this phenomenom throughout metrics like the Standard Deviation (SD) or the Normalized SD (NSD) of class-wide error. Once again, these metrics reveal that adversarial training indeed results in greater disparities across classes in both standard and robust performance compared to natural training.

Potential Causes

While the authors succeeded in identifying the problem of fairness, they also aimed to understand where it was coming from. From what they observed, it seems that the fairness issue particularly disadvantages classes that are inherently more challenging to classify. Adversarial training in fact tends to increase the standard errors for “harder” classes (like “cat”) significantly more than for “easier” classes (such as “car”).

1.2 Theoretical Demonstration

From the experiments on the potential causes of the fairness issue, the authors made the following hypotetis: Adversarial training makes hard classes even harder to classify or classify robustly. In this section, we review the theoretical proof of this hypothesis.

For this analysis, we place ourselves in the case of a binary classification task, using a mixed Gaussian distribution to create two classes with distinct levels of classification difficulty. Thus, adversarial training does not notably lower the average standard error but it shifts the decision boundary in a way that favours the ’easier’ class at the expense of the ‘harder’ class.

Prerequisites

- The classification model, denoted $f$, is a mapping $f : \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}$ from input data space $\mathcal{X}$ and output labels $\mathcal{Y}$ defined as $f(x) = \text{sign}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} + b)$ with parameters $\mathbf{w}$ and $b$

- The standard error for a classifier $f$ generally is: $R_{\text{nat}}(f) = \Pr(f(\mathbf{x}) \neq y)$

- The robust error for a classifier $f$ generally is: $R_{\text{rob}}(f) = \Pr(\exists \delta, |\delta| \leq \epsilon, \text{s.t. } f(\mathbf{x} + \delta) \neq y)$ (the probability of a perturbation existing that would cause the model to produce an incorrect prediction)

- The standard error conditional on a specific class $\{Y = y\}$ is represented by $R_{\text{nat}}(f; y)$

Theoretical Experiment

We generate a simple example of the binary classification task that we presented at the beginning of section 1.2. The data therefore comes from two classes $\mathcal{Y} = { \{-1, +1\}}$, with each class’ data following a Gaussian distribution $\mathcal{D}$ centered on $-\theta$ and $\theta$ respectively. It is important to specify that there is a $K$-factor difference between the variance of the two classes defined as follows: $\sigma_{+1} : \sigma_{-1} = K : 1$ and $K > 1$.

The authors then use the theorem stating that:

Theorem: In the case of a data distribution $D$ like the one above, the optimal linear classifier $f_{\text{nat}}$ which minimizes the average standard classification error is: $$ f_{\text{nat}} = \arg\min_f \Pr(f(\mathbf{x}) \neq y) $$.

With that theorem and after computations, the authors prove that the class “$+1$” as a larger standard error than the class “$-1$”.

Overall, this result shows well that the class “$+1$”, characterized by a larger variance, tends to be more challenging to classify than the class"$-1$"; a result confirming the hypothesis initially made.

2. Model

In this section, we present the Fair Robust Learning model (FRL).

2.1 Fairness Requirements

The authors introduced the concepts of Equalized Accuracy and Equalized Robustness, emphasizing the importance of providing equal prediction quality and resilience against adversarial attacks across different groups. To achieve this balance, the authors propose a Fair Robust Learning (FRL) strategy. This framework addresses fairness issues in adversarial training by aiming to minimize overall robust error while ensuring fairness constraints are met. They separate robust error into standard error and boundary error, allowing independent solving of the unfairness of both errors. [ref 7]

The training objective thus becomes minimizing the sum of standard error and boundary error while adhering to fairness constraints that ensure no significant disparities in error rates among classes. Techniques from prior research are leveraged to optimize boundary errors during training.

2.2 Practical Algorithms

This section explores effective methods to implement and address the challenges outlined in the training objective, such as the Reweight strategy. In order to implement it, Lagrange multipliers are introduced, denoted as $φ = (φ_{nat}^{\text{i}}, φ_{bndy}^{\text{i}})$ where each multiplier corresponds to a fairness constraint. These multipliers are non-negative and play a crucial role in the optimization process.

The approach involves forming a Lagrangian, represented by the function $L(f, φ)$, which combines the standard error ($R_{\text{nat}}(f)$) and boundary error ($R_{\text{bndy}}(f)$) terms along with the fairness constraints. The Lagrangian acts as a guide for the optimization process, helping to balance the trade-off between minimizing errors and satisfying fairness requirements.

$$ \scriptsize{ L(f, \phi) = R_{\text{nat}}(f) + R_{\text{bndy}}(f) + \sum_{i=1}^{Y} \phi_{\text{nat}}^i \left( R_{\text{nat}}(f, i) - R_{\text{nat}}(f) - \tau_1 \right)^+ + \sum_{i=1}^{Y} \phi_{\text{bndy}}^i \left( R_{\text{bndy}}(f, i) - R_{\text{bndy}}(f) - \tau_2 \right)^+ } $$

The optimization problem is then framed as a max-min game between the classifier $f$ and the Lagrange multipliers $φ$. The objective is to maximize the fairness constraints while minimizing the Lagrangian function, which encapsulates both standard and boundary errors.

On the other hand, the Reweight strategy presents a limitation particularly in mitigating boundary errors for specific classes. While upweighting the cost for standard errors ($R_{\text{nat}}(f, i)$) can penalize large errors and improve performance for disadvantaged groups, solely upweighting the boundary error ($R_{\text{bndy}}(f, i)$) for a class doesn’t effectively reduce its boundary error.

To overcome this challenge, the Remargin strategy introduces an alternative approach by enlarging the perturbation margin ($\epsilon$) during adversarial training. This strategy is inspired by previous research showing that increasing the margin during adversarial training can enhance a model’s robustness against attacks under the current intensity.[ref 8]

Specifically, the Remargin strategy involves adjusting the adversarial margin for generating adversarial examples during training, focusing on specific classes where boundary errors are significant. This adjustment aims to improve the robustness of these classes and reduce their large boundary errors ($R_{\text{bndy}}(f, i)$).

3. Experimentation

In this section, we reproduce the experimental methodology and setup used to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Fair Robust Learning (FRL) framework in constructing robust deep neural network (DNN) models.

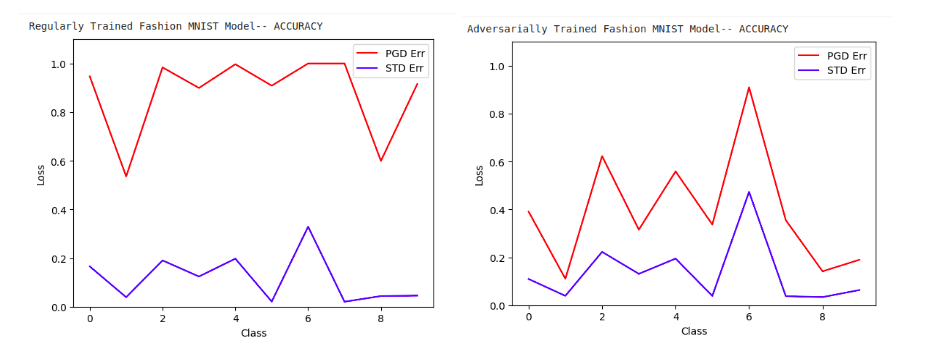

Firstly, we train a fairly simple model on the Fashion MNIST dataset, then we test out torchattack’s PGD on our naturally trained model, Then we will adversarially train the same architecture to see if we can identify this unfairness.

As we can see above, the naturally trained model has low standard error, but high PGD error. The adversarially trained model, in contrast, has a much lower PGD error, but higher standard error, and higher disparity between the classes.

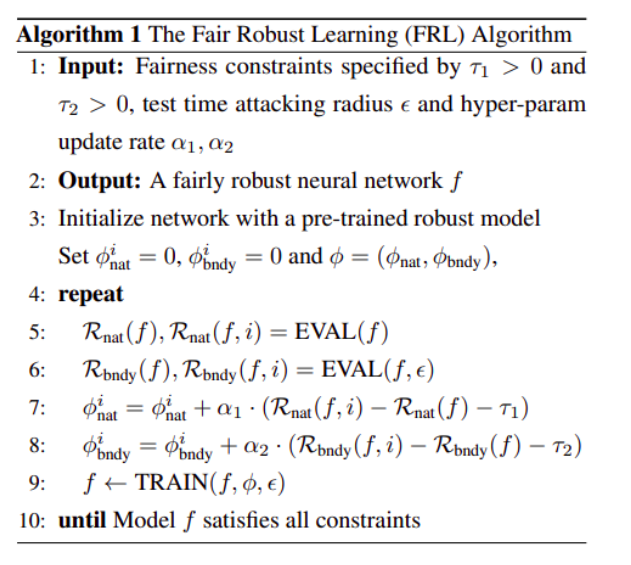

Second, we implement the FRL algorithm (Reweight strategy) which formulates the learning problem as a cost-sensitive classification that penalizes those classes which violate fairness. Essentially, we create multipliers that up or down weight the loss of classes based on how fair or unfair they are with respect to the average across all classes.

The following is the FRL Algorithm outlined in the paper:

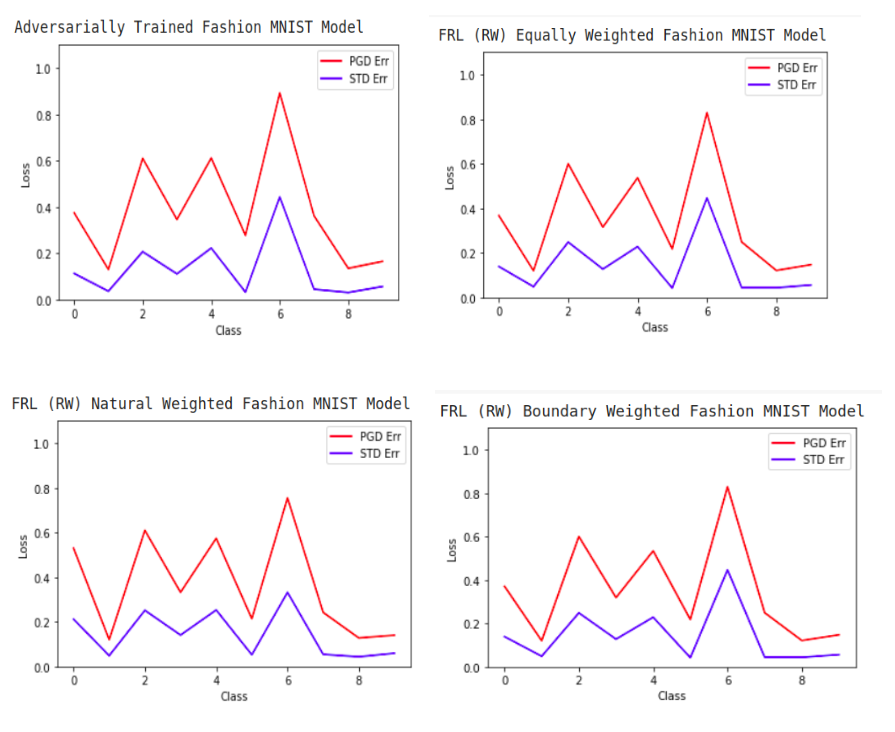

We made a setup to run the process 3 times: once with equal alpha values, once with an alpha ratio that favors the natural error, and one with an alpha ratio that favors the boundary error.

In accordance with the authors of the paper, we find that the alpha ratio that favors the natural error is successful in preventing the unfairness of the standard error in the model, and does help somewhat with the unfairness of the PGD error. On the other hand, we notice that the algorithm struggles to improve the worst-case boundary error, leading to disparities in robustness performance across different classes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the studied article discusses the development and implementation of Fair Robust Learning (FRL) strategies to address fairness concerns in adversarial training of deep neural networks. The objective of these strategies is to achieve both equalized accuracy and robustness across different classes.

The Reweight strategy aims to minimize overall robust error while adhering to fairness constraints by adjusting training weights based on class-wise errors while the Remargin strategy enlarges the perturbation margin during adversarial training to improve robustness and reduce boundary errors.

Finally, The FRL framework combines these strategies to mitigate fairness issues and improve model performance across various classes. These approaches represent promising steps towards achieving fairness in robust deep learning models.

References

[1] Han Xu, Xiaorui Liu, Yaxin Li, Anil K. Jain, Jiliang Tang1. To be Robust or to be Fair: Towards Fairness in Adversarial Training. 2021.

[2] Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., and Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. 2014.

[3] Morgulis, N., Kreines, A., Mendelowitz, S., and Weisglass, Y. Fooling a real car with adversarial traffic signs. 2019.

[4] Sharif, M., Bhagavatula, S., Bauer, L., and Reiter, M. K. Accessorize to a crime: Real and stealthy attacks on state of-the-art face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 acm sigsac conference on computer and communications security, pp. 1528–1540, 2016.

[5] Krizhevsky, A., Hinton, G., et al. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. 2009.

[6] He, H. and Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering, 21(9):1263–1284. 2009.

[7] Zhang, H., Yu, Y., Jiao, J., Xing, E. P., Ghaoui, L. E., and Jordan, M. I. Theoretically principled trade-off between robustness and accuracy. 2019.

[8] Tramer, F., Behrmann, J., Carlini, N., Papernot, N., and Ja- ` cobsen, J.-H. Fundamental tradeoffs between invariance and sensitivity to adversarial perturbations. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 9561–9571. PMLR. 2020.