Privacy Amplification: How Decentralization Enhances Data Protection

Alexia Avakian, Kenza Erraji, and Constantin Guillaume

M2DS - 2024 2025

1. Introduction: Rethinking Privacy in the Digital Age

Imagine a world where AI models learn from data without ever seeing it. Your personal information remains private while still contributing to medical research, smart city planning, and financial security. Traditional privacy techniques often rely on trusted third parties, creating potential security risks.

The research paper Privacy Amplification by Decentralization presents a new approach called Network Differential Privacy (Network DP), which enhances privacy through decentralization. Instead of relying on a central entity to enforce privacy guarantees, this method leverages the structure of decentralized networks to naturally amplify privacy.

This blog post explores the key insights from the paper, progressing from fundamental concepts to advanced applications.

2. Why Privacy Matters in Machine Learning

Machine learning algorithms often require access to vast amounts of data, making privacy a critical concern. This data must be protected from unauthorized access and inference, while still allowing legitimate users to communicate and share information.

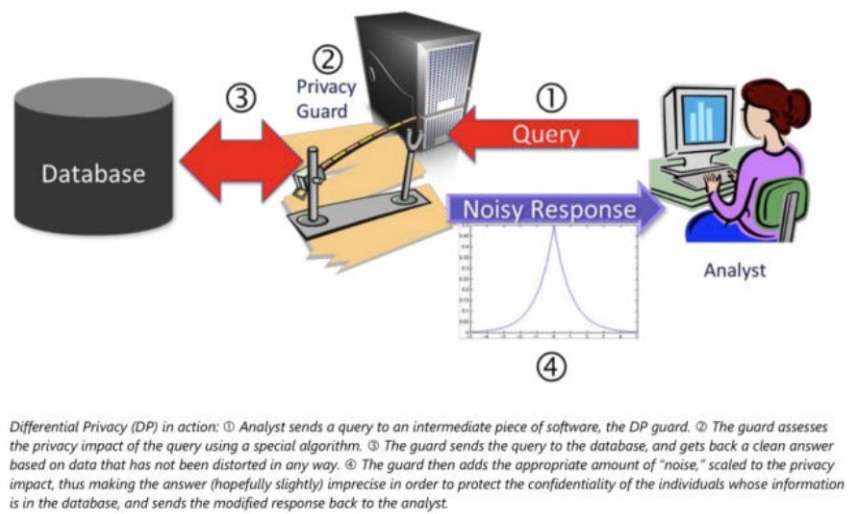

A widely used privacy-preserving technique is Differential Privacy (DP), which ensures that an individual’s data cannot be inferred, even if an attacker has access to the dataset. This is achieved by adding controlled noise before sharing the data.

As shown in the image, a privacy guard acts as an intermediary, ensuring that the output remains privacy-preserving. The guard assesses the privacy impact of the query and injects noise to mask individual contributions before responding.

However, applying DP in decentralized systems presents challenges:

- Local DP forces users to add noise to their data before sharing, which enhances privacy but significantly reduces accuracy.

- Other privacy models rely on a trusted entity to collect and aggregate data while ensuring privacy. If this entity is compromised, all data security is lost.

This trade-off has led researchers to explore Network DP, which naturally amplifies privacy in decentralized architectures.

3. Privacy Models: From Simple to Advanced

Before diving into Network DP, let’s compare two differential privacy models to understand their strengths and weaknesses.

3.1. Local Differential Privacy (LDP)

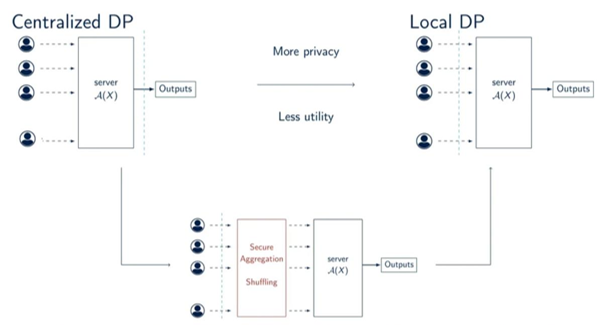

In Local Differential Privacy, every user aims to protect their own shared data to prevent any potential adversary from detecting it. This model ensures privacy by applying strong noise locally to the data before it leaves the user’s device. This way, the data is protected from any non-legitimate user trying to access it, as the noise hinders its accuracy.

While this guarantees strong privacy protection, the downside of this excessive randomness is that data utility is significantly degraded as the number of users increases. Indeed, the data is made less useful for everyone, even for legitimate users.

3.2. Intermediate Trust Models

To prevent the limitations of LDP regarding data utility, other solutions have been developed, such as Intermediate Trust Models. These are models that are initially based on LDP in order to protect privacy, but reduce the amount of noise used to ensure a higher accuracy. Two main approaches have been developed:

- Using cryptography to aggregate the contribution of the users. In this solution, users encrypt their local data and only the final result of their contributions is decrypted. Because only this final result can be viewed, this method needs less noise to ensure privacy.

- Shuffling the set of user messages. In this solution, less noise is applied to the data since the link between users and contributions has been randomized and their origin cannot be determined anymore.

The downside of these Intermediate Trust Models is that they have a higher computational cost.

3.3. Network Differential Privacy (Network DP)

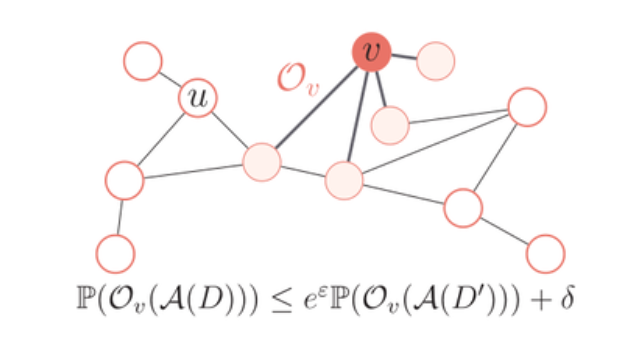

Network DP introduces a fully decentralized approach where privacy is amplified by limiting each user’s visibility to only their direct neighbors in a communication network. Instead of introducing excessive noise to data, the privacy guarantee is achieved through restricted information flow, making it harder for any participant to reconstruct the original dataset.

4. How Does Network DP Work?

Unlike classic LDP, where each user shares noisy updates with a central server, Network DP operates in a fully decentralized manner to limit the exposure of private data. Each user communicates only with their direct neighbors in a network graph, meaning that no single entity has full visibility over the data.

One of the key ideas in Network DP is that the way data flows in the network impacts privacy guarantees. Sparse networks provide stronger privacy guarantees compared to fully connected graphs, as data is shared in smaller isolated fragments. The paper explores different network topologies and demonstrates how privacy naturally improves in decentralized systems.

A useful analogy is a group of people whispering secrets in a crowded room. If each person only hears fragments of the conversation, it becomes nearly impossible to reconstruct the full message. Network DP works the same way: users only see local fragments of data, preventing attackers from accessing complete information.

Another important mechanism in Network DP is the use of random walks for data propagation. Instead of sending information directly to a central aggregator, data is passed along a sequence of random nodes, effectively masking its origin and making it increasingly difficult to track individual contributions. The longer the random walk, the more difficult it becomes for an adversary to trace back individual data points, enhancing privacy. This diffusion-based approach reduces the need for excessive noise injection while preserving utility in decentralized computations.

The authors propose a token-based decentralized computation model, where a “token” moves across the network. Each user who receives the token updates it based on their local data and then passes it along. Since no one sees the full dataset, privacy is naturally strengthened.

5. Network Topology and Privacy Amplification

The effectiveness of Network DP depends not only on decentralized communication but also on the underlying structure of the network graph. Sparse networks, such as ring or expander graphs, provide stronger privacy guarantees, as users only exchange data with a few immediate neighbors. This prevents any single entity from accumulating enough data to breach privacy.

In contrast, highly connected graphs may weaken privacy since more participants gain visibility into the data exchange process. The paper explores how varying topologies affect privacy amplification, highlighting that well designed network topologies can amplify privacy without requiring additional noise injection, making Network DP a compelling alternative to traditional differential privacy techniques.

6. Technical Insights: How Effective is Network DP?

One of the key contributions of the paper is proving mathematically that Network DP improves privacy guarantees through decentralization. In simpler terms, just by having users communicate only with their neighbors in a network (without needing to add extra noise), the system becomes more privacy-preserving.

These results are supported by theoretical proofs based on information leakage analysis. The main idea is to model how much private information an adversary can infer based on what each user sees in the network. Because users only observe local information from their neighbors, the overall visibility, and therefore the potential for leakage, is significantly reduced. The theorems formalize this by bounding the adversary’s knowledge and showing how these bounds shrink as the network grows.

This said, privacy amplification in Network DP follows an O(1 / √n) improvement compared to LDP O(√n), meaning that as the number of users increases, privacy naturally improves.

For decentralized stochastic gradient descent (SGD), the privacy amplification effect is even stronger, scaling as O(ln n / √n).

7. Experimental Results: Network DP in Action

The paper evaluates Network DP against existing DP models through several experiments, particularly in machine learning tasks such as classification and decentralized stochastic gradient descent (SGD). The key findings include:

- Network DP maintains a privacy-utility trade-off similar to Centralized DP but without requiring a central authority, making it viable for fully distributed systems.

- Compared to Local DP, Network DP achieves better accuracy by reducing the need for excessive noise.

- Network DP scales efficiently with an increasing number of users, making it practical for large scale decentralized networks, such as federated learning (each user keeps their own data local and contributes only with the results of local computations).

8. Security Considerations: Potential Attacks and Collusion

While Network DP provides strong privacy guarantees, it is not entirely immune to security threats and attacks. One of the primary concerns is collusion, where multiple participants in the network work together to reconstruct hidden data. If a group of malicious nodes strategically shares their observed data fragments, they might be able to infer sensitive information, breaking the privacy guarantees provided by the system. This risk is particularly relevant in decentralized environments where there is no central authority to monitor or regulate data sharing.

To counter these risks, researchers have proposed several mitigation strategies. One approach is to design network topologies that limit information overlap, ensuring that no small subset of users has enough visibility to infer private data. In fact, if the network is sparsely connected, collusion becomes harder because no small subset of users can reconstruct a significant portion of the data.

Additionally, random walks can be introduced for information propagation, ensuring that information moves randomly across the network which helps to prevent any single group of nodes from reconstructing a user’s data.

These defenses make Network DP more resilient to malicious behavior, ensuring that privacy amplification remains effective even in the presence of coordinated attacks. However, as decentralized networks continue to grow in scale and complexity, ongoing research is required to strengthen privacy mechanisms against more sophisticated adversaries.

9. Applications: Where Can Network DP Be Used?

Network DP is particularly useful in decentralized applications where privacy is a concern. One of the key areas explored in the paper is federated learning, where models are trained across distributed users without sharing raw data. Network DP enhances privacy in federated learning by reducing reliance on a central server while maintaining accuracy.

10. How Network DP Compares to LDP

| Privacy Model | Centralized? | Privacy Amplification | Utility Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local DP | No | None | High noise, low accuracy |

| Network DP | No | Strong (from decentralization) | Low noise, high accuracy |

11. Conclusion: The Future of Privacy-Preserving AI

Network DP represents a significant advancement in privacy-preserving AI by removing the need for centralized trust and reducing the dependency on excessive noise injection. By leveraging decentralized communication, it naturally amplifies privacy without compromising accuracy, offering a scalable alternative to traditional privacy-preserving mechanisms like Local DP.

As AI regulations become stricter and the demand for secure data processing grows, Network DP has the potential to serve as a key framework for privacy-preserving decentralized systems. Its ability to balance strong privacy guarantees with high utility makes it particularly relevant for federated learning, decentralized AI training, and other distributed computing applications. However, challenges remain, particularly in optimizing privacy amplification across different network topologies and mitigating adversarial threats such as collusion.