Adversarially Reweighted Learning

Fairness without Demographics through Adversarially Reweighted Learning

Authors: Pierre Fihey & Guerlain Messin

Table of Contents

- Fairness issues in ML and AI

- The privacy of demographic’s data

- The Adversarial Reweighted Learning Model

- An Hypothesis: Protected Groups are Correlated with Both Features and Labels

- Computational identifiability of protected groups

- The Rawlsian Max-Min Fairness principle

- The ARL objective

- The Model Architecture

- Results analysis

- Conclusion

This is a blog post about the paper Fairness without Demographics through Adversarially Reweighted Learning, published by P. Lahoti et al. in 2020 and available here.

Fairness issues in ML and AI

As Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence algorithms are increasingly developed to aid and automate decision-making, it is crucial that they provide ethical, fair and discrimination-free results. However, discriminative biases are now found in many facets of AI and ML and affect many possible applications.

Such biases can be found in NLP applications, where we can see that generative AIs often associate certain genders or ethnic groups with professions. In computer vision, the lack of diversity in the training data also induces numerous discriminatory biases, since we can see that the algorithms’ performances differ according to age, gender and ethnic group, which can lead to unfair treatments. Machine Learning models, used in decision-making processes from loan approvals to job applications, can inherit historical biases present in their training data, resulting in unfair outcomes.

The root of these biases lies in the historical prejudices and inequalities that are inadvertently encoded into the datasets used to train AI and ML models. These datasets often reflect the societal, cultural, and institutional biases that have existed over time. As a result, when AI and ML technologies are trained on such data, they risk mirroring and amplifying these biases instead of offering neutral, objective outputs. It is therefore vital to focus on AI fairness to enable the development of technologies that will benefit everyone fairly and equitably.

The privacy of demographic’s data

Strict regulations established by laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) severely restrict the collection of demographic data, including age, gender, religion and other personal attributes. This legal framework, designed to protect individual privacy and data rights, poses a problem for the study of discriminatory bias in algorithms, since it becomes almost impossible to measure. This situation creates a real paradox, since protecting personal data conflicts with limiting discrimination and promoting fairness for ML and iA algorithms.

In this blog, we’ll look at the paper Fairness without Demographics through Adversarially Reweighted Learning, published by Google’s 2020 research team to propose a method for improving the fairness of AI models despite the lack of demographic data. Indeed, while much previous works have focused on improving fairness in AI and ML, most of these works assume that models have access to this protected data. Given the observations made above, the problem this paper attempts to address is as follows: How can we train a ML model to improve fairness when we do not have access to protected features neither at training nor inference time, i.e., we do not know protected group memberships?

The Adversarial Reweighted Learning Model

An Hypothesis: Protected Groups are Correlated with Both Features and Labels

While access to the protected features is often impossible, the authors of this paper assume that there is a strong correlation between these variables and the observable features X as well as the class labels Y. Although these correlations are the cause of the fairness problems faced by ML algorithms, they represent a real advantage here, as they can help to identify these protected groups and thus to evaluate and correct possible discrimination biases.

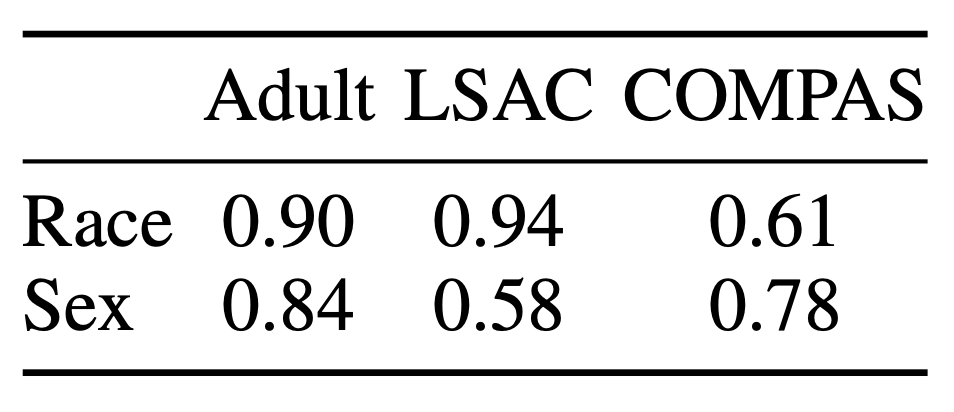

The authors have shown that this hypothesis is frequently verified. For example, they were able to predict the race and gender of individuals in the Adults and LSAC Datasets with high accuracy from unprotected features and labels.

This assumption therefore implies that protected groups can be computationally identifiable. It is on this notion of computational identifiability that the model proposed by Google’s research team is based to outperform previous work.

Computational identifiability of protected groups

Computational identifiability refers to the ability to algorithmically identify specific subgroups or patterns within a dataset based on certain criteria, using computable functions. Mathematically, this notion is defined as follows:

For a family of binary functions $F$, we say that a subgroup $S$ is computationally-identifiable if there is a function $f : X \times Y \rightarrow \text{{0, 1}}$ in $F$ such that $f(x, y) = 1$ if and only if $(x, y) \in S$.

This function typically maps input data to a binary outcome, indicating protected subgroup membership. While many previous works have used this principle of computational identifiability, the model presented in this article differs in that it does not require these subgroups to be present in the input space, but also in its objective. While most work has focused on reducing the efficiency gap between each subgroup, the ARL model aims to increase efficiency for these subgroups, while considering that this should not be at the expense of the other groups. Indeed, the authors have decided to follow the Rawlsian Max Min fairness principle, which we present below.

The Rawlsian Max-Min Fairness principle

In philosophy, the Rawlsian Max Min principle of distributive justice is defined by John Rawls as maximizing the welfare of the most disadvantaged member of society. In a mathematical context, this can be translated as maximizing the minimum utility U a model has across all groups s ∈ S. We adopt the following definition:

Definition (Rawslan Max-Min Fairness): Suppose $H$ is a set of hypotheses, and $U_{D_s}(h)$ is the expected utility of the hypothesis $h$ for the individuals in group $s$, then a hypothesis $h^* $ is said to satisfy Rawlsian Max-Min fairness principle if it maximizes the utility of the worst-off group, i.e., the group with the lowest utility. $$h^* = argmax_{h \in H} min_{s \in S} U_{D_s}(h)$$

The Maxmin Rawlsian principle inherently accepts the existence of inequalities, as its core aim is not to ensure uniform outcomes across all groups but rather to maximize the overall utility, particularly focusing on enhancing the welfare of the least advantaged. This is what will enable our model to obtain truly relevant results, and we’ll now see how it adapts this principle to define a loss function to be minimized during training.

The ARL objective

To adapt this Rawlsian principle to a Machine Learning task, the authors decided to set up a MinMax Problem. A minmax algorithm is a mathematical problem defined in game theory. Its aim is to optimize the worst possible scenario for a player, assuming that the opponent plays optimally. The aim is now to minimize the highest loss, i.e. the loss of the most disadvantaged protected group. This new objective function is defined as follows:

$$J(\theta, \lambda) := min_{\theta} max_{\lambda} \sum_{s \in S} \lambda_s L_{D_s}(h)$$ $$= min_{\theta} max_{\lambda} \sum_{i=0}^{n} \lambda_{s_i} l(h(x_i), y_i)$$

With $l(.,.)$ the cross-entropy loss and lambda the weights that maximize the weighted loss of protected groups. To solve this minmax problem, the authors set up a special architecture consisting of two neural networks, a learner and an adversary.

The Model Architecture

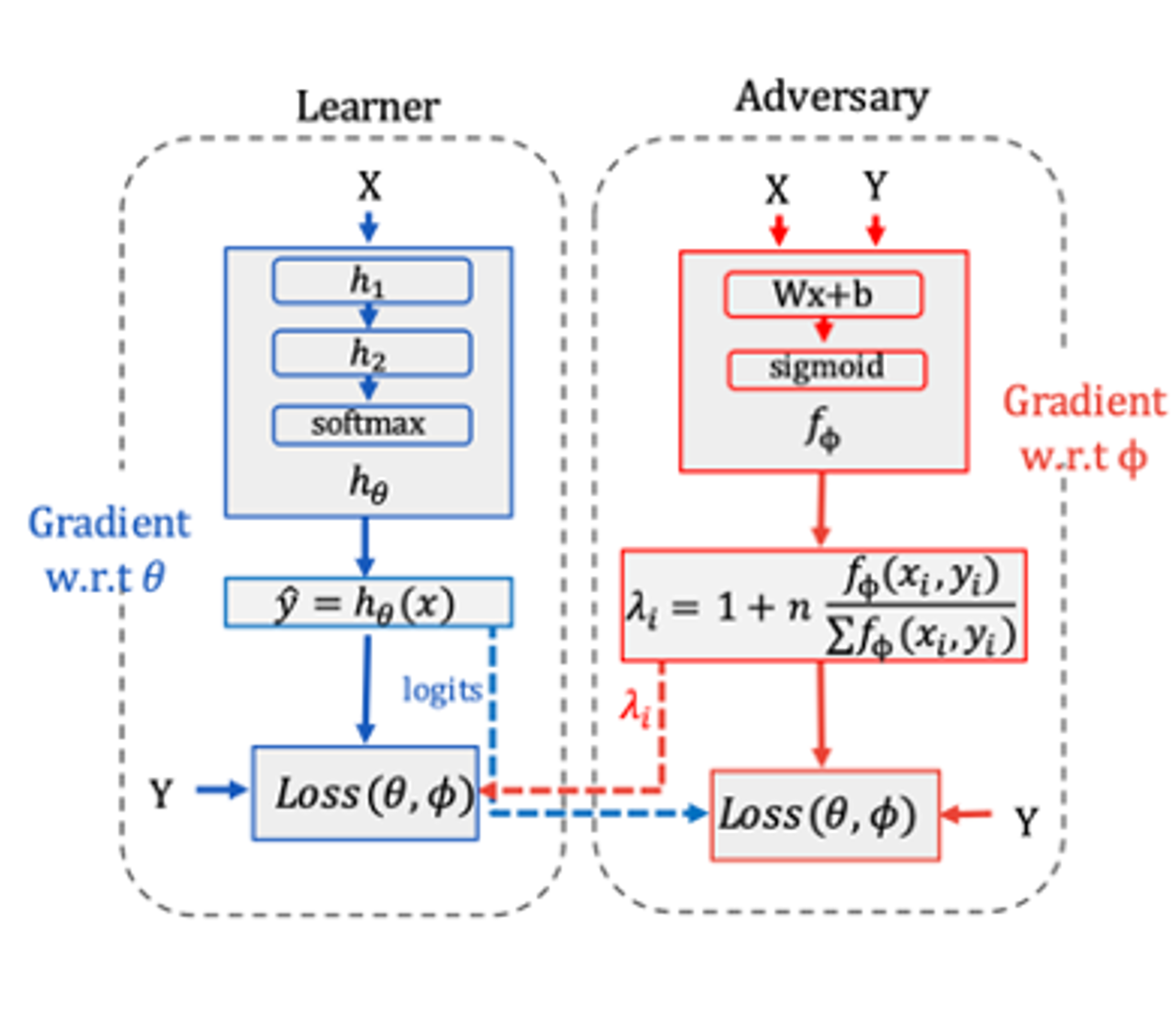

As previously announced, the authors therefore decided to implement the Adversarial Reweighted Learning (ARL) approach, training two models alternately.

The learner optimizes for the main classification task, and aims to learn the best parameters θ that minimizes expected loss.

The adversary learns a function mapping $f_\phi : X \times Y \rightarrow [0, 1]$ to computationally-identifiable regions with high loss, and makes an adversarial assignment of weight vector $\lambda_\phi : f_\phi \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ so as to maximize the expected loss.

The learner then adjusts itself to minimize the adversarial loss: $$J(\theta, \phi) = min_{\theta} max_{\phi} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \lambda_{\phi}(x_i, y_i) \cdot l_{ce}(h_\theta(x_i), y_i)$$

To ensure that the loss function is well defined, it’s crucial to introduce specific constraints on the weights used in the loss function. Ensuring these weights are non-negative, prevent zero values to include all training examples, and are normalized, addresses potential instability and promotes uniform contribution across the dataset.

$$\lambda_{\phi}(x_i, y_i) = 1 + n \cdot \frac{f_{\phi}(x_i, y_i)}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} f_{\phi}(x_i, y_i)}$$

The authors have implemented these two networks using standard feed-forward network. The learner is a fully connected two-layer feed-forward network with 64 and 32 hidden units in the hidden layers, with ReLU activation function. For small datasets, the adversary which performs the best is a linear model.

Results analysis

This section provides a detailed examination of the results obtained from our implementation of the Adversarial Reweighted Learning (ARL) model. We replicate the experiments conducted by Lahoti et al. and present the outcomes of our implementation. Furthermore, we analyze the significance of the results through a comprehensive evaluation.

Reproducibility

We first reproduce the results reported by Lahoti et al. using their TensorFlow implementation. However, due to the absence of optimal hyperparameters, we utilize default parameters for our runs. As a result, our AUC scores are lower than those reported in the original paper. For instance, the average AUC for the Adult dataset in Lahoti et al.’s work is 0.907, whereas our run yields an AUC of 0.497. Similarly, for the LSAC dataset, Lahoti et al. report an AUC of 0.823, whereas we obtain 0.518. The COMPAS dataset also exhibits a similar trend, with Lahoti et al. reporting an AUC of 0.748, compared to our result of 0.536. Subsequent experimentation with optimal parameters from TensorFlow implementation demonstrates improved performance, although AUC scores remain lower than those presented in the original paper.

Replicability

We replicate the experiments using our PyTorch implementation of the ARL model with optimal hyperparameters obtained through grid-search. Comparing the AUC scores with Lahoti et al.’s results reveals close alignment for the Adult and LSAC datasets. However, a slightly larger difference is observed for the COMPAS dataset. Notably, all AUC metrics for the COMPAS dataset are lower than the baseline model presented by Lahoti et al. This discrepancy suggests potential challenges with dataset size, leading to increased variance in results. Nonetheless, our PyTorch implementation demonstrates consistency with Lahoti et al.’s findings, highlighting the robustness of the ARL model across different implementations.

Significance Evaluation

We conduct significance tests to evaluate the performance improvement of our PyTorch-implemented ARL model compared to a simple baseline model. Despite observing notable improvements in fairness metrics, none of the p-values obtained are less than 0.05. Consequently, according to established significance criteria, the performance enhancement achieved by our ARL model is not statistically significant. This finding underscores the need for further investigation into the efficacy of adversarial learning methods in enhancing fairness without demographic information.

Conclusion

In this study, we critically examined the paper “Fairness without Demographics through Adversarially Reweighted Learning” by Lahoti et al., focusing on reproducibility, replicability, and the significance of reported results. While encountering challenges in reproducing Lahoti et al.’s results due to parameter settings and dataset characteristics, we successfully replicated the experiments using our PyTorch implementation. Despite demonstrating consistency with the original findings, our significance tests indicate a lack of statistical significance in the performance improvement achieved by the ARL model. This prompts further inquiry into the suitability of adversarial learning approaches for addressing fairness concerns in machine learning without relying on demographic data.

Annexes

References

[1] Lahoti, P., Beutel, A., Chen, J., Lee, K., Prost, F., Thain, N., Wang, X., & Chi, E. H. (2020). Fairness without demographics through adversarially reweighted learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.13114.

[2] Veale, M., & Binns, R. (2017). Fairer machine learning in the real world: Mitigating discrimination without collecting sensitive data. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 2053951717743530.

[3] Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1982). The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology, 143(1), 29-36.

[4] Hanley, J. A., & McNeil, B. J. (1983). A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology, 148(3), 839-843.

[5] Dua, D., & Graff, C. (2019). UCI machine learning repository.

[6] Kim, M. P., Ghorbani, A., & Zou, J. (2019). Multiaccuracy: Black-box post-processing for fairness in classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 247-254).

[7] Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., … & Bengio, Y. (2014). Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems, 27, 2672-2680.

[8] Paszke, A., Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J., Chanan, G., … & Chintala, S. (2019). PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (pp. 8024-8035).

[9] Kamishima, T., Akaho, S., & Sakuma, J. (2011). Fairness-aware learning through regularization approach. In 2011 IEEE 11th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (pp. 643-650). IEEE.