Neural Networks Forget to Forget: Fixing the Memory Problem With Tensor Decomposition

Based on the paper “Activation Map Compression through Tensor Decomposition for Deep Learning” by Nguyen et al.

Authors: Akshita KUMAR, Florent BLANC

Date: 27 March 2025

Have you ever wondered why you still distinctly remember the first time someone made fun of you at school or the birthday gift your parents gave you 15 to 20 years ago? The human brain is capable of storing countless pieces of information and memories in an intricate web of about 86 billion neurons, each consisting of thousands of connections! If it’s difficult to grasp the magnitude of that number, consider this: if we tried to unwrap and lay out all that information, it would require about 2.5 petabytes of memory! Yet, somehow, all of it fits neatly inside our heads, in a space smaller than a watermelon!

Now, imagine if our brains tried to save space the way Mr. Bean packs his suitcase—randomly tossing out items, keeping only one shoe, or draining half the toothpaste into the sink. In that case, you might end up remembering your best friend’s birthday but confusing it with a dramatic event from Elon Musk’s life that was all over the news two months ago. Clearly, our brains have mastered compression in a way that doesn’t compromise accuracy (or mix up childhood nostalgia with internet chaos).

Deep learning models, in many ways, attempt to emulate this incredible ability of the human brain by mimicking the complex web of connections to enable the sharing of information. Neural networks have revolutionized everything from image recognition to natural language processing by learning complex data patterns. However, one challenge they have conventionally faced is storing all this information in a limited space—they require an enormous amount of memory and computational power. Training deep networks can take terabytes of storage, and running them efficiently demands specialized hardware.

Neural networks consist primarily of two backbones: network weights and neuron activations, which are sufficient to define and distinguish between a simple network making a random guess about whether I am likely to be involved in money laundering and one that carefully considers years of my financial records to decide whether I am a safe candidate for a bank loan. While the size of weight matrices might seem daunting for deep neural networks, the major bottleneck in terms of memory size is actually the storage of activations, which, as per backpropagation Equation (2), is required for weight updates. If you’re a first-time reader, you might be wondering: why not just eliminate these non-linear activation functions and try to make the weights and architecture universal enough to model every imaginable scenario? To answer this, picture yourself driving on a winding mountain road filled with sharp turns and steep inclines. If you were to drive in a straight line, no matter how beautiful the scenery is, you’d quickly find yourself off the road and tumbling down into the valley. Since life doesn’t give you a chance to backpropagate to correct your mistakes, perhaps in your next life, you might learn to navigate the terrain better! Similarly, a network devoid of activation functions is no more capable of surviving the complexities of real-world data than a simplistic linear logistic regression model, no matter how deep the architecture is.

Now, if you were to try to fit this dreadfully large memory-requiring activation map into a microcontroller, you would be no different from Mr. Bean frantically trying to pack his suitcase. The indispensability and large memory requirements of these nonlinear activations have paved the way for research into compressing activation maps when computational resources are limited. Just like our brains optimize memory storage without losing vital details, researchers are exploring ways to shrink deep learning models without making them as absurdly dysfunctional as cutting a pair of trousers into shorts. In this post, we’ll dive into activation map compression through tensor decomposition, a method (Nguyen et al., \url{https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.06346}) that enables deep networks to fit into small devices while maintaining their performance. We’ll start by gradually explaining all concepts required to understand the idea, building up from the motivation and proceeding into the technical details. Let’s unpack this and explore how deep learning is learning to travel light!

1/ Memory Bottleneck in Backpropagation

Training a deep neural network is a bit like learning to drive. You don’t just memorize how to turn the steering wheel — you constantly adjust based on feedback. If you overshoot a turn, your brain registers the mistake, corrects your hand movements, and hopefully, you don’t end up in a ditch. In deep learning, this feedback loop is called backpropagation, a process where the network tweaks its internal parameters to minimize errors over time. In this section, we explore in a bit more detail, the reason behind the huge increase in memory requirements when performing this parameter correction.

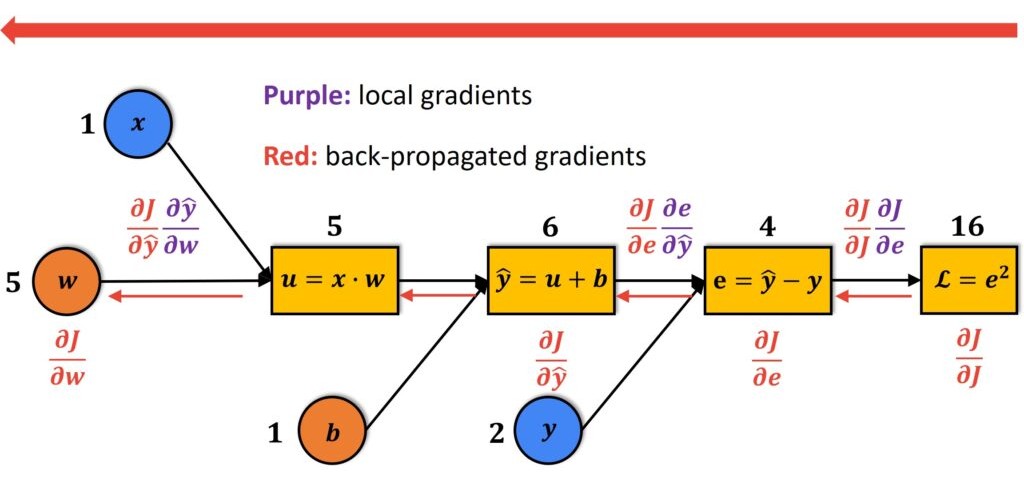

The primary idea behind backpropagation is simple — use the chain rule for updating model parameters.

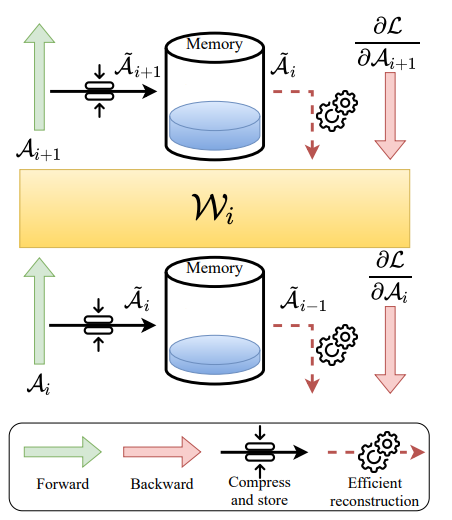

In Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), each layer takes in an activation tensor $A_i$, applies a linear transformation followed by the non-linear activation function, and finally produces an output activation $A_{i+1}$.

During training, backpropagation employs convolution operations to compute the gradients, which determine how much each weight $W_i$ and activation $A_i$ contributes to the final loss. Mathematically, we can express it as:

$$ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_i} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial A_{i+1}} \cdot \frac{\partial A_{i+1}}{\partial W_i} = \text{conv} \left( A_i,\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial A_{i+1}} \right) \tag{1} $$

where $ \mathcal{L} $ represents the loss function, and $ \text{conv}(\cdot) $ and $ \text{conv}_{\text{full}}(\cdot) $ are convolution operations.

We make an important observation from these formulas: to update a weight, we need both the original activation and the gradient of the next layer, which means that we must store all these tensors - the primary difference between backpropagation and inference. And that is exactly where things get messy, leading to a memory crunch during backpropagation.

Now, let’s think about this in a different light. Imagine you’re a movie director. Instead of keeping only the final version of each scene, you save every take, every angle, and every tiny adjustment in full resolution. Your hard drive fills up within hours! This is similar to what happens with deep neural networks—they store all activations for potential gradient calculations, even though not all of them are equally important. And not surprisingly, activations are high-dimensional tensors, meaning they can grow in size ridiculously fast. A single activation map has dimensions $ B \times C \times H \times W $ (batch size × channels × height × width). If a network has dozens of layers, storing all these activations at once quickly overflows memory, especially on small, low-power devices like smartphones or IoT sensors. This is why deep networks are often trained in the cloud — but sending data to external servers brings its own headaches, like privacy risks and latency issues.

So, what is a good way to fix this digital hoarding problem and pack our network efficiently into a small storage space? There are two main strategies:

Weight compression – Reducing the size of the model itself.

Activation compression – Cutting down the size or the number of activations stored during training.

While there have been several exciting efforts towards reducing the space occupied by the network weights - sparsification (dropping a fraction of less significant weights), quantization (reducing parameter precision to save memory), knowledge distillation (using pretrained large networks as “teachers” that guide the training of smaller and more compact “student” networks) etc, the authors of this paper focus on the second approach, and the following sections will allow you to discover the intricacies of how exactly they do so.

2/ Tensor Decomposition

Among different compression techniques, tensor decomposition is emerging as a promising solution. It reduces large activation maps to smaller and structured representations, by storing only the most informative parts of the map while discarding redundant or uninformative components. This is based on a mathematical concept called low-rank approximation, which was originally developed for signal processing but is now making waves in deep learning.

2.1/ Breaking Down a Matrix: the SVD trick

Let’s first look at the (second) simplest version of a tensor - a 2D matrix. The technique called Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) breaks down a matrix $A$ into three parts:

Now, before you get too excited about SVD, take a step back! SVD works only for 2D matrices! And activation maps in CNNs are in fact 4D tensors (batch size × channels × height × width), i.e $A \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times C \times H \times W}$.

To apply SVD, we first have to reshape our activation tensor into a 2D matrix: $A \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times (CHW)}$. Then, we obtain:

Truncating each decomposed component to only the top $ K $ values, we obtain a low-rank approximation of $ A $:

Did you realise what just happened? We significantly reduced the amount of storage space required, from $\mathcal{O}(BCHW) \text{ to } \mathcal{O}(K(B + CHW))$.

Well, this is a bit like stuffing a big fat McD burger into a small tiffin box. It surely allows you to savour your favorite meal wherever you want, but ends up mixing the sauces and popping out veggies.

Similarly, in CNNs, this reshaping operation destroys spatial patterns and mixes information from different dimensions, leading to inefficiency.

2.2/ Towards HOSVD: The Higher-Dimensional Packing Strategy

To avoid this, we turn to Higher-Order Singular Value Decomposition (HOSVD)—the tensor-ified sister of SVD, that works directly on multi-dimensional tensors without flattening them. Instead of trying to squish everything into a single matrix, HOSVD compresses each dimension separately, maintaining important spatial relationships.

Given an activation tensor $ T $ of shape $ M_1 \times M_2 \times \cdots \times M_n $, HOSVD decomposes it as follows:

- $ S $ is the core tensor, which represents a compressed version of $ T $,

- $ U^{(j)} $ are orthogonal factor matrices that capture the most significant variations along each dimension $ j $,

- $ \times_j $ denotes the mode-$ j $ product, which multiplies the tensor $ S $ by the factor matrix $ U^{(j)} $ along the $ j $th individual dimension instead of treating the tensor as a giant matrix. Since different dimensions (batch, channels, height, width) carry different types of information, HOSVD allows us to compress each dimension optimally.

We truncate both the core tensor S and the factor matrices along each mode to retain only the most significant components:

In practice, we limit ourselves to the 4-mode decomposition (i.e $n=4$). This approach helps achieve higher compression, reducing the memory requirement while preserving the network’s ability to learn effectively, implying that deep learning models can run with less memory without becoming as dysfunctional as a half-packed Mr. Bean suitcase!

2.3/ Unpacking the Math: How Backpropagation Works with Tensor Decomposition

Now that we’ve seen how tensor decomposition helps reduce memory usage, let us now address the secrets of how this dreadful-looking $i$-mode product can be backpropagated. Equations 1 and 2 show that the activation tensors appear only in the computation of gradient with respect to the weights. To express it in a single line, the gradient of the loss function with respect to weight matrix $W_i$ can be written as:

If you’re feeling brave enough to dive into the depths of how this formula is derived, buckle up for some gradient magic and expand the following section. But if you’re just here for the big picture and don’t want to dream of summations and convolutions tonight, feel free to continue to the next section!

Step 1: The Usual Backprop Formula

Click to see the math of this step!

The standard weight update rule for a convolutional layer requires computing the gradient of the loss with respect to the weights:

where $ \mathcal{I} $ is the padded input and $ \Delta \mathcal{Y} $ is the gradient of the output.

Step 2: Tensor Decomposition – Breaking It Down

Click to see the math of this step!

The following equation looks daunting, but it is nothing more than the matrix product expression of what \ref{eq:4}) refers to!This means that instead of storing $ \mathcal{I} $ directly, we store its compressed components $ U^{(j)} $ and $ \hat{S} $.

Step 3: Restoring the Input in Backward Pass

Click to see the math of this step!

Coming to the part of the algorithm that allows the network to go back and corrrect it mistakes, we now put together the decomposed components to reconstruct the input:Here, $ U^{(3)} $ and $ U^{(4)} $ undergo vertical padding. This step ensures that we reconstruct the original shape needed for backpropagation.

Step 4: Rewriting the Gradient Computation

Click to see the math of this step!

We now substitute this back into the weight update equation and reorganize terms:At this stage, we have effectively transformed the weight update process into a series of smaller matrix multiplications and convolutions, reducing the computational burden.

This entire derivation ultimately leads to the final gradient computation in equation 3.

3/ Experimental Validation

It’s one thing to talk about activation compression in theory, but does it actually work in practice? To find out and test the authors’ claims, the authors put HOSVD to the test across multiple deep learning architectures — MobileNetV2, ResNet18, ResNet34, and MCUNet — and compared its performance with other activation compression strategies. These models vary in depth, design, and computational footprint, making them ideal test subjects to see how activation compression affects memory, computation, and accuracy.

3.1/ Experimental Setup

To make the evaluation structured and fair, compression techniques were tested on both classification and segmentation tasks.

Classification: Fine-tuning pre-trained models using two strategies:

- Full fine-tuning: Fully fine-tuning models pre-trained on ImageNet (“teachers”) on downstream datasets.

- Half fine-tuning: Splitting ImageNet into non-i.i.d. partitions and training in a federated learning framework — using one partition each for pre-training and fine-tuning.

Semantic Segmentation: Models trained on Cityscapes (an urban streets view dataset) were fine-tuned to work on Pascal-VOC12 (a 20-category image dataset for pixel-level segmentation tasks), a task that requires fine-grained spatial details.

Instead of setting compression levels arbitrarily, the explained variance was controlled, which is the direct “remote control” for the amount of information that is retained while reducing the activation size. This ensures that memory vs. accuracy trade-offs are compared on equal terms across different techniques.

3.2/ How Much Can We Compress Without Hurting Accuracy?

When compressing activations using HOSVD, one of the key decisions is choosing how much variance to retain. Too little variance makes the network lose crucial details, and too much of it makes the memory reductions negligible.

Key Findings on Explained Variance:

- Less than 20% of components capture more than 80% of the variance. This means we can throw away a lot of redundant data while keeping performance intact.

- Compression scales non-linearly: keeping 80–90% of variance gives a huge reduction in storage while maintaining accuracy.

- Below 80% variance, accuracy drops fast. Beyond 90%, we hit diminishing returns — almost no accuracy gain, but memory costs start rising.

What’s the best trade-off between accuracy and compression?

An explained variance of 0.8 and 0.9 was settled on as the sweet spot.

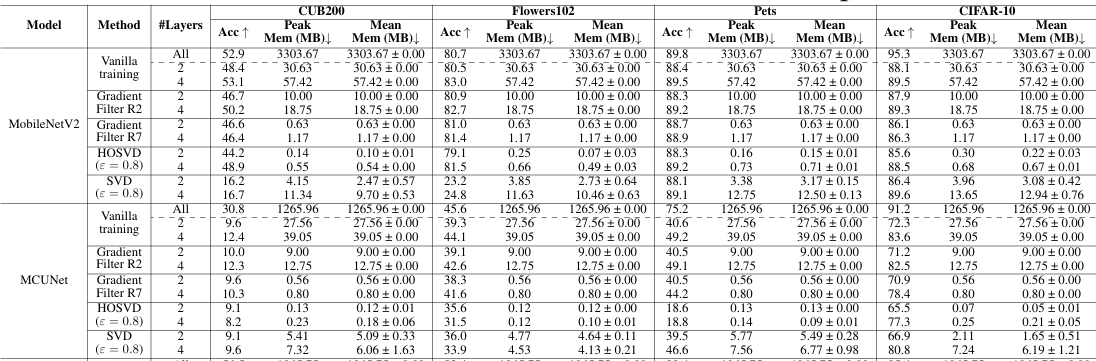

3.3/ Main Results: What the Authors Say

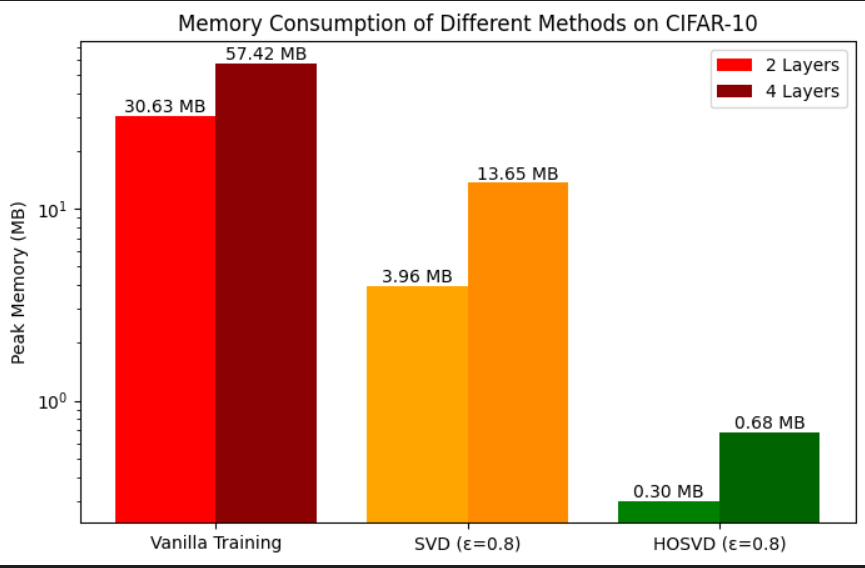

- HOSVD consistently outperforms SVD and gradient filtering — better accuracy and smaller memory requirement; so for accurate classification, the multi-modal structure of the activation tensor must be preserved.

- At the same level of memory consumption, HOSVD reduces the amount of activation storage by 18.87 times on average.

- As compared to SVD, HOSVD enhances accuracy by up to 19.11%, which validates that preserving the multi-dimensional activation structure is indeed crucial.

In fact, HOSVD works great not just for classification — it also maintains performance across segmentation tasks while significantly reducing memory use! This makes it a great candidate for memory-constrained applications that still require fine-grained spatial details (e.g., medical imaging, autonomous driving).

3.4/ Main Results: Our Attempt at Replication

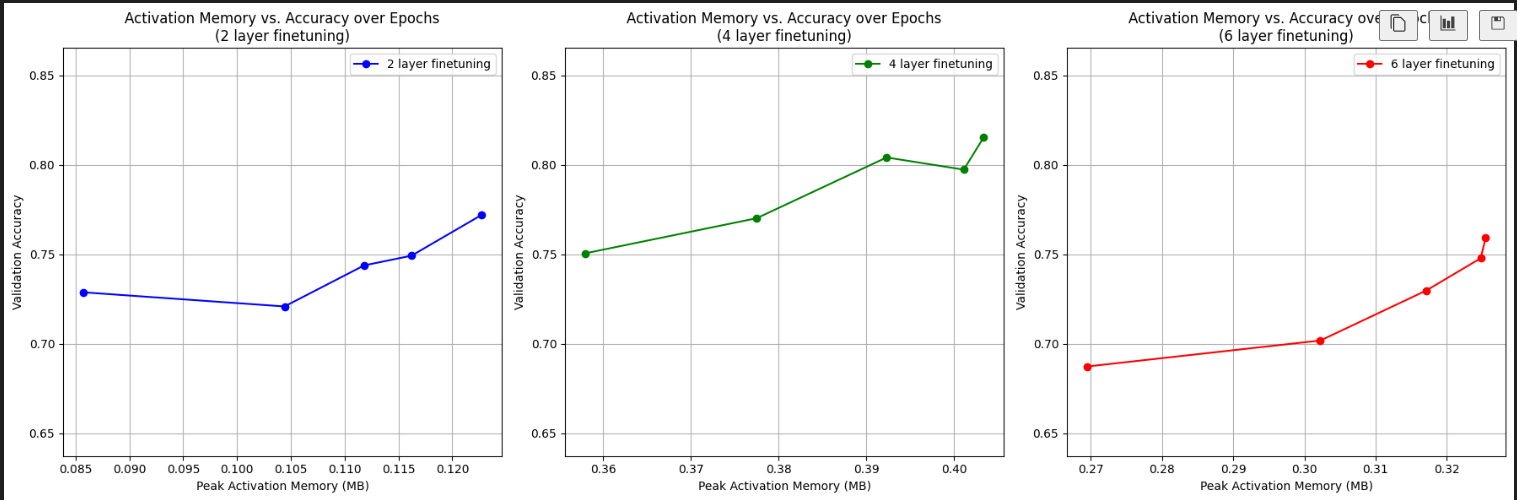

To verify the authors’ claims, we rolled up our sleeves and conducted an independent test on a system equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-1255U processor, 16 GB RAM, and 4 memory cores. We chose MobileNetV2—the lightest of the architectures—and fine-tuned it using HOSVD on CIFAR-10 for 5 epochs, setting the explained variance to 0.8. The results? Surprisingly strong with an interesting trend:

- Going from 2 to 4 layers increased validation accuracy by 4% but also raised peak memory by 0.3MB — a reasonable trade-off.

- However, increasing to 6 layers actually hurt accuracy, despite consuming more memory! This suggests that excessive compression led to information loss propagating across layers — similar to the degradation seen in gradient filtering techniques. In other words, there is a fine balance between compression and performance.

Reproduction Table

| Num Finetune | Val Acc | Peak Mem | Mean Mem | Std Mem | Mean ± Std | Total Mem | Time/Epoch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.7721 | 0.1227 | 0.1082 | 0.0142 | $0.11 \pm 0.01$ | 0.5409 | 40 min |

| 4 | 0.8154 | 0.4034 | 0.3864 | 0.0189 | $0.39 \pm 0.02$ | 1.9322 | 50 min |

| 6 | 0.7592 | 0.3254 | 0.3078 | 0.0234 | $0.31 \pm 0.02$ | 1.5390 | 90 min |

Table 1: Reproduction Experiments — Memory usage and validation accuracy for different number of layers fine-tuned.

3.5/ Key Takeaways: What We Learned

- HOSVD beats SVD and gradient filtering in terms of the tradeoff between memory and accuracy for activation compression.

- Compression beyond 90% explained variance isn’t worth it; accuracy stops improving, but memory costs continue to grow exponentially.

- Our reproduction experiments were feasible on a CPU only because HOSVD drastically reduces peak memory usage — down to 0.3MB compared to 30MB required for vanilla training — allowing us to bypass the need for high-end hardware while still yielding meaningful results — showing just how well this approach can work in more resource-constrained environments.

Why does HOSVD win?

Unlike SVD, which flattens activation tensors and loses spatial correlations, HOSVD keeps tensor relationships intact, resulting in higher accuracy for the same memory budget.

Still skeptical? Try it yourself! Check out our CPU-friendly implementation :

Beware! The original code may not work with newer versions of PyTorch Lightning; several functionalities have deprecated. Our version resolves the compatibility issues.

4/ Embedded AI: What Lies Ahead?

The results are clear: HOSVD-based activation compression is a game changer for making deep learning models more memory-efficient without compromising their accuracy. By keeping the most essential information while trimming away redundancy, we’ve seen how compression can reduce activation storage drastically, making it possible to run complex models even on resource-limited devices.

But what’s next? AI models are already pushing the limits of what’s possible on embedded hardware. Today, deep learning runs on devices as small as a few millimeters in size - Edge TPUs, MCUs with less than 1MB of RAM, and smartphones packing neural processing units (NPUs). And it’s not just about running models efficiently—compression techniques like this are making on-device learning a reality. Instead of relying on massive cloud servers, models can now adapt and learn locally, whether it’s a smartwatch fine-tuning its activity tracking, a smartphone enhancing its voice recognition, or an AI assistant getting smarter without sending personal data to the cloud. The ability to learn on the go, without bloated memory requirements, brings AI one step closer to mimicking the adaptability of the human brain.

Perhaps, one day, deep learning models will successfully bridge this gap to achieve the kind of seamless efficiency our brains naturally posses. Until then, activation compression is one giant leap toward making AI as frugal and intelligent as nature itself.