A Groupe Fairness

No Retraining? No Problem! FRAPPÉ’s Bold Approach to AI Fairness

Authors of the blogpost: Arij Hajji , Rouaa Blel

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Why Fairness in AI Matters

- How FRAPPÉ Works

- FRAPPÉ vs. Traditional Fairness Methods

- Why FRAPPÉ is Important

- Real-World Example

- Experimenting

- Final Thoughts

- What Do You Think About FRAPPÉ?

- References

- About the Authors

Introduction

Imagine being confident in your abilities and expertise when you apply for your ideal job, only to have your application denied—not due to your qualifications, but rather to biases an AI system learned from past data. It’s infuriating, unjust, and regrettably becoming a bigger issue as AI-driven choices in criminal justice, lending, and employment become more prevalent.

Imagine being confident in your abilities and expertise when you apply for your ideal job, only to have your application denied—not due to your qualifications, but rather to biases an AI system learned from past data. It’s infuriating, unjust, and regrettably becoming a bigger issue as AI-driven choices in criminal justice, lending, and employment become more prevalent.

Correcting biased AI models can be a difficult task. Traditional methods often involve re-training the entire model, which can be costly, time-consuming and sometimes impossible . But can’t we find a simpler way?

Presenting FRAPPÉ, a methodology that eliminates bias in AI without requiring retraining. A novel method called FRAPPÉ (Fairness Framework for Post-Processing Everything) transforms our understanding of fairness in machine learning. Rather than modifying the entire model, it provides a more efficient solution by adjusting the output to ensure fairness. We will examine the main ideas, contributions, and practical applications of this ground-breaking study in this blog., you can check out the original paper, FRAPPÉ: A Group Fairness Framework for Post-Processing Everything, by Alexandru Ţifrea, Preethi Lahoti, Ben Packer, Yoni Halpern, Ahmad Beirami, and Flavien Prost.

Why Fairness in AI Matters

Important choices including bank approvals, employment recruiting, and medical diagnosis are increasingly being made using AI algorithms. These mechanisms can, however, perpetuate current disparities and disproportionately impact particular populations when they reflect biases.

Ensuring group fairness—the notion that demographic groupings like age, gender, and ethnicity are treated fairly and equally—is one of the primary ethical concerns in AI research. Fairness is far from easy to achieve, though. Equal opportunity, statistical parity, and equalized odds are only a few of the many ways that fairness can be interpreted, and each one has its own trade-offs between predictability and justice.

When Fairness in AI Went Wrong: The Amazon Hiring Scandal

When we think about a good exemple of AI bias we can think about when Amazon created a tool to assess job appplications. With the tech sector generally employing more men, the model was trained on previous employment data and discovered trends favoring male applicants. As a result, resumes containing terms such as “feminine” (e.g. “women’s chess club”) and indicating a preference for environments with a higher proportion of men were devalued by AI. Amazon in 2018 put an end to the usage of this method, showing what biases could do to our society and especially in job selection. This case highlights the need for robust bias mitigation techniques and the importance of fairness in AI.

Fairness Mitigation Strategies in AI

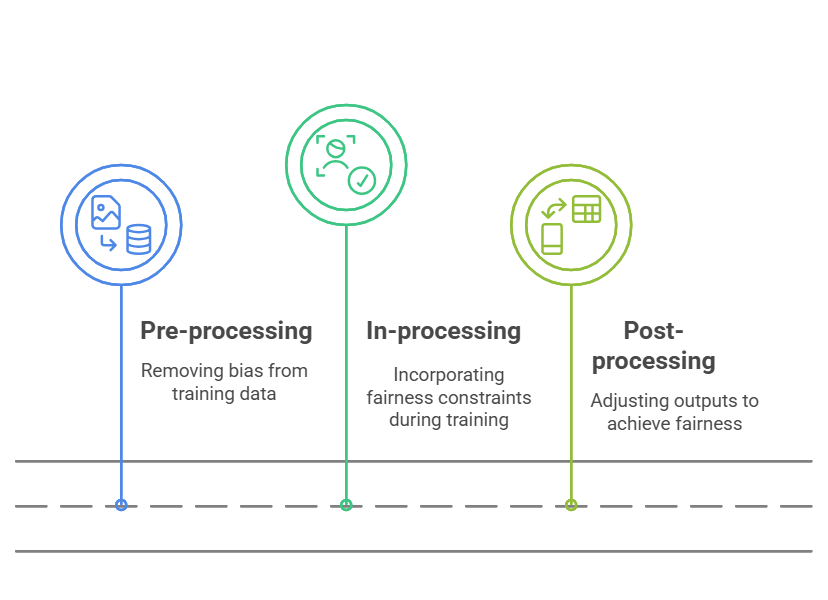

To address these biases, AI fairness strategies typically fall into three main categories:

In-Processing: This strategy involves modifying the model during its training phase to directly integrate fairness constraints. While effective, it can be computationally expensive and often requires retraining the entire model, which may not be practical in all situations.

Post-Processing: These methods apply adjustments to the model’s outputs after predictions have been made. It offers greater flexibility since it doesn’t require altering the original model. However, these methods are often limited to specific fairness criteria and may not apply universally.

Pre-Processing: This approach involves adjusting the training data before it’s used to train the model. By altering the data to reduce bias before training, pre-processing aims to create a fairer dataset. However, this approach can also introduce challenges, such as data distortions or loss of valuable information.

How FRAPPÉ works ?

Instead of relying on explicit group-dependent transformations that depend directly on sensitive attributes (e.g., gender, race), FRAPPÉ applies an additive correction based on all covariates ( x ). This ensures fairness while maintaining predictive accuracy.

Mathematical Formulation of FRAPPÉ

At its core, FRAPPÉ modifies a base model’s prediction fbase(x) by applying a fairness correction term TP P (x), leading to:

ffair (x) = fbase(x) + TP P (x)

where:

- fbase(x) represents the original model output.

- TPP (x) is an additive term learned through post-processing to correct fairness discrepancies.

This transformation enables FRAPPÉ to achieve fairness objectives without modifying the model’s internal structure.

Theoretical Justification

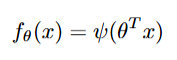

To establish the validity of this approach, we consider generalized linear models (GLMs), where predictions take the form:

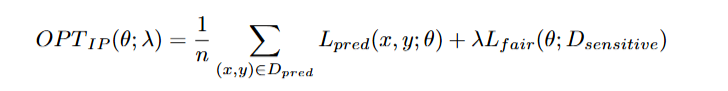

for model parameters θ and a link function ψ (like identity function for linear regression, sigmoid for logistic regression). In fairness-constrained optimization, we often minimize:

where:

- Lpred is the predictive loss (like mean squared error, logistic loss).

- Lfair is a fairness penalty.

- λ controls the fairness-accuracy trade-off.

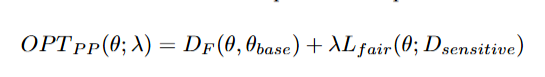

FRAPPÉ recasts this as a bi-level optimization problem:

where:

- θbase is the solution to the unconstrained prediction problem.

- DF(θ, θbase) is a Bregman divergence term ensuring predictions remain close to the original model.

The key insight is that minimizing OPTIP and OPTPP leads to identical fairness-error trade-offs, proving that FRAPPÉ’s post-processing approach is theoretically equivalent to traditional in-processing fairness methods.

FRAPPÉ vs. Traditional Fairness Methods

| Feature | FRAPPÉ | Traditional Fairness Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Model Agnosticism | Works with any machine learning model, whether black-box or interpretable. | Typically tied to specific model architectures or requires model modifications. |

| Fairness Flexibility | Can adapt to various fairness criteria (equal opportunity, statistical parity, etc.). | Often focuses on a single fairness definition, limiting flexibility. |

| Sensitive Data Usage | Does not require sensitive data (e.g., race, gender) during prediction. | Many methods rely on sensitive data during prediction, which can raise ethical concerns. |

| Efficiency | Post-processing adjustment makes it faster and less resource-intensive. | Often requires full model retraining, which is computationally expensive. |

Why FRAPPÉ is important

Efficiency:

Using FRAPPÉ the training cost can be reduced upto 90% compared to in-processing approaches, since FRAPPÉ only learns a small layer of correction instead of the entire model.

-Flexibility: In the case where statistical parity is mandatoryr instead of equal opportunity FRAPPÉ is the solution.

-Privacy: For FRAPPÉ the storage or extraction of sensitive demographic data is not crucial or obigatory, as it works without group labels at the time of prediction.

Real-World Example

Let’s take in mind a hiring algorithm ,it basically scores applicants based on their resumes. An exemple of historical bias means female applicants womm receive lower scores on average. Traditionally, we’d need to retrain the whole model to correct this.

Using FRAPPÉ, the original model can remain untouched — we just add a fairness correction layer that adapts scores to ensure fairness across genders. This is faster, cheaper, and works even if we didn’t train the original model.

Experimenting

Reproducibility and Potential Difficulties

Careful consideration of model setup, hyperparameter selection, and dataset preprocessing are necessary to replicate these findings. Potential bias is indicated by the baseline model’s notable differences in classification accuracy and error rates between Sex1 (likely male) and Sex0 (likely female). By equating false positive and false negative rates across groups, the fairness-aware model effectively reduces these discrepancies utilizing the FRAPPÉ framework. However, ensuring consistent replication of these findings poses challenges.

Final Thoughts

When retraining a model isn’t feasible, FRAPPÉ offers a practical, adaptable, and efficient solution to ensure fairness in AI systems. By decoupling model learning from fairness adjustments, it makes it easier to incorporate fairness without overhauling existing models.

For anyone working in ethical AI, data science, or policy-making, FRAPPÉ stands out as a powerful tool. It allows for the development of fairer technologies that are not only faster but also more scalable.

What Do You Think About FRAPPÉ?

Could this innovative framework be the key to making fairness mitigation in AI more practical and scalable? We’d love to hear your thoughts—feel free to share your opinions!

References

Alexandru Țifrea, Preethi Lahoti, Ben Packer, Yoni Halpern, Ahmad Beirami, Flavien Prost. FRAPPÉ: A Group Fairness Framework for Post-Processing Everything. ICML 2024. arXiv Link

About the Authors

Arij Hajji

M2 Data Science, Institut Polytechnique de Paris

arij.hajji@telecom-paris.fr

Rouaa Blel

M2 Data Science, Institut Polytechnique de Paris

rouaa.blel@ensae.fr